Simply put, money is something you can exchange in return for goods and services. As you’ll learn below, knowing how much money is in an economy at any given point in time is useful information.

As for money supply, that’s generally defined as all the physical cash—that is, banknotes and coins—that’s circulating through an economy at any given time, as well as bank deposits.

Understanding Money Supply

The first thing to know when it comes to money supply is that there’s no universally accepted definition. The way money gets measured varies between economies. In all economies, there are several money supply measurements that get monitored. This is the case in Australia, for example.

Why have multiple ways to measure money supply? Because money can take the form of many different types of financial instruments. (A financial instrument is really just any contract that has monetary value and can be traded.) It all depends on what does and doesn’t get classified as money.

When figuring out whether a financial instrument should belong to a certain definition of money supply, liquidity plays a big factor. (Put simply, liquidity refers to the ease with which something can be sold for cash.)

The most liquid financial instruments that exist are physical cash and bank deposits. Each day, you use these two instruments as a medium of exchange to buy goods and services. In any widely used measurement of money supply, physical cash and bank deposits are counted.

Who influences money supply?

In most countries, central banks are able to influence how much money is circulating through the economy. They do this by conducting monetary policy. Central banks such as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) have several monetary policy tools at their disposal to speed up and slow down money supply growth. One of these is quantitative easing.

Money Supply Measures

As covered above, there’s no “best” way to measure the supply of money. Variation exists between what central banks classify as money. For the rest of this resource, we’ll use the RBA’s measures of money supply as examples.

The RBA tracks five different measures of money supply: currency, base money, M1, M3 and broad money. (Each of these is called a ‘money aggregate’.)

As the RBA puts it: “In general terms, currency, M1, M3 and broad money represent money-like liabilities of Australian financial intermediaries with respect to Australian households and businesses that are not financial intermediaries.”

Currency

This money aggregate is simply just banknotes and coins held by the private sector, excluding banks. Currency is the RBA’s narrowest definition of money supply.

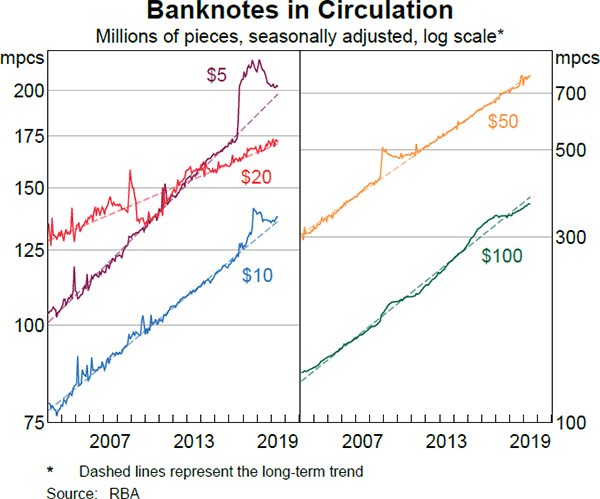

In terms of banknotes, the RBA stated in its 2019 annual report that there were 1.6 billion in circulation as at Jun. 30, 2019. The nominal value of these banknotes totalled A$80 billion.

Money base

The money base represents currency and currency held by banks. It also includes deposits of banks with the RBA and other RBA liabilities to the private non-bank sector. (Money base is also called ‘monetary base’, ‘base money’, ‘M0’, ‘narrow money’ and ‘reserve money’. They all mean the same thing!)

M1 money aggregate

M1 is a relatively liquid measure of money that includes currency and all transaction deposits at banks, credit unions and building societies (‘CUBS‘). What gets counted in M1 are instruments you can—without penalty or limitation—directly access whenever you need.

M3 money aggregate

The M3 money aggregate includes everything in M1 plus less liquid bank deposits such as term deposits with maturities of one year or less.

Broad money

Broad money is the RBA’s broadest money aggregate. It typically uses this measure to estimate the entire supply of money within the Australian economy.

The RBA defines broad money as “currency plus ADI deposits from the non-AFI private sector, plus other short-term liquid AFI liabilities held by the non-AFI private sector.” This just means broad money captures an even wider net of financial instruments that can be viewed as having money-like characteristics.

(An ADI is an authorised deposit-taking institution that is not registered as a bank, credit union or building society. The acronym AFI stands for ‘all financial intermediaries’, which includes ADIs.)

Money Supply & The Economy

Money plays an important role in any modern economy. When the supply of money is growing too slow or fast, it can spell trouble for inflation and economic output—as measured by gross domestic product (‘GDP‘)—which can in turn lead to unemployment rises and diminished living standards across society as a whole.

Why Understanding Money Supply Helps You Grasp Bitcoin

As you’ve seen in the above charts, the supply of money constantly grows. The reason why this happens is because of actions taken by central banks and commercial banks.

As the supply of money increases, the purchasing power of your cash deteriorates. If you put $100 aside in the 1990s and went to spend it today, you’d find that the amount of stuff you can buy with that $100 is nowhere what it was all those years ago.

Getting an understanding of this helps you appreciate a unique feature of Bitcoin. That is, there is a known maximum supply of 21 million bitcoin. Today, everyone knows that at roughly the year 2140, there will be 21 million bitcoin circulating and that no more will be coming into existence.

Having a capped supply is in direct contrast to today’s most widely used form of money: fiat currency. When you store your wealth in cash, you’re trusting that your country’s government and central bank can successfully manage inflation; a task that many countries—such as Iran, Argentina, Zimbabwe, Lebanon and Venezuela—are failing at. The result? Citizens seeing the value of their life savings wither away due to hyperinflation.